Oak trees benefit vineyards

Grapegrowers learned about the Valley oak at a recent seminar

Grapegrowers learned about the Valley oak at a recent seminar

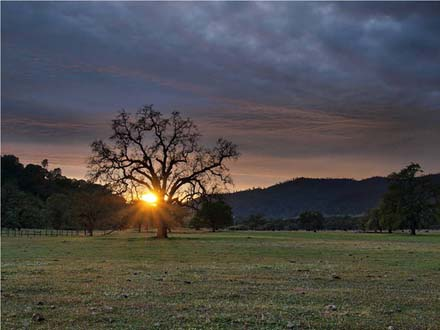

Napa, Calif.--A majestic Valley oak tree in the midst of a vineyard is a striking icon of California’s wine country, but oaks and vineyards need care if both are to prosper.

A recent seminar sponsored by the University of California Cooperative Extension and the Napa Valley Sustainable Winegrowing Group examined this co-existence and its implications for growers and the general community.

Long before Europeans--or even Native Americans--arrived in California’s coastal valleys, the landscape featured native perennial grasses--which stayed green during the summer--with single giant Valley oaks and clusters of trees providing virtual islands valuable to wildlife and the environment.

Later, humans also took advantage of the trees for shade and shelter as well as sustenance; they used the acorns for flour after leaching out the harsh tannins. Also--unknown to them--the trees exhaled oxygen while sequestering carbon and reducing erosion.

In 1811, when Europeans arrived in Napa Valley, an estimated 20,000 oaks dotted the valley floor, averaging one for every two acres. Settlers cut many to plant grains, other crops and eventually vines, but left trees around their homes for shade and in unplanted areas. They built their towns like St. Helena and Oakville in oak groves, too.

Cutting of trees accelerated as vines and orchards replaced row crops in the later 1800s. By 1940, only 2,000 oaks were left. Now, in the wake of further vineyard and housing development, the number stands at about 1,000.

Oaks bring significant value to the environment. Aside from the aforementioned benefits, they are beautiful--an important consideration for an area largely dependent on tourists—and they increase the economic value of home sites and other property.

Nevertheless, oaks can compromise vineyards. Obviously, they require significant space: The soil must not be planted or compacted in their root zone, which is typically at least as large as the canopies that can stretch 70 to 80-feet. Their shade can slow or even prevent grapes from ripening, leading to unwanted vegetal flavors.

That said, many growers seek to protect their oaks and plant new ones, particularly along property boundaries to create attractive road corridors; and in vernal pools, on steep slopes, along creeks and in other areas unsuitable for vines.

Napa wants more oak

The workshop covered both maintaining old oaks and regenerating individual trees and groves, although one contrarian forest expert suggested those steps have little environmental impact and instead recommended concentrating on separate oak forests.

The interest in oaks has spawned a movement among environmentalists and others to “re-oak” Napa Valley. Napa County has adopted a voluntary oak woodland management plan that encourages protection and replanting of native oaks.

The plan lists the values of the oaks:

• Cultural/historical

• Flood protection

• Erosion control

• Water clarity and quality protection

• Air quality and carbon sequestration

• Plant and wildlife health

• Scenic and public recreation

• Enhanced property value

It also lists the threats to oaks, including lack of regeneration due to low production of acorns, poor seeding conditions, herbivores, water stress and ground water levels.

Another threat is increasingly severe fires, rather than the historic fast but less intense fires set by lightning or natives, and of course, tree cutting for development. Sudden Oak Disease is a concern for some species, particularly Coastal live oaks. Scientists are also still unsure of the impacts of climate change, including migration of species such as destructive pests.

A first priority is to maintain existing trees and groves. For growers, this means leaving adequate space around the trees, not compacting the soil in the root zone, not changing water flow patterns, and, of course, not digging under or irrigating maturing trees. A common problem is using the root zone as turning space for farm equipment.

Fortunately, oak trees are fairly easy to establish; blue jays would blanket the valley with their buried acorns if we didn’t stop them, it seems.

The two most common oak varieties along the coast regions are the deciduous Valley oak, the largest variety, and the evergreen Coast live oak with its holly-like spiked leaves.

Planting and care

The best approach is to choose acorns turning brown on nearby trees (fallen acorns deteriorate quickly), and plant them about an inch deep in the late fall when rains start. They can be refrigerated for a while before planting.

They don’t generally need irrigation. They respond well to it, but spread out their roots instead of sending deep taproots, so if you start irrigating, you’ll probably have to continue. Old trees can drop branches, particularly if they’re too well watered, and grow too fast to gain strength.

Many animals eat seedlings and even saplings, so they may need protection in the form of grow tubes and wire cages.

You can buy saplings to plant, but they have deep roots to contend with; it’s best to get local varieties adapted to your conditions. The trees grow quite fast from acorns anyway, reaching 10 to 12-feet in a few years, and depending on the variety, ultimately perhaps 75-feet tall.

Grapegrowers typically plant oaks along roads and boundaries on the north side of vineyards to minimize shading vines, and around buildings to shade them and provide shade for people. The deciduous Valley oak provides cooling shade in the summer, but drops the canopy for warmth in the winter.

Planting in clusters--remembering their eventual size--is both attractive and environmentally beneficial if you have sufficient space.

Property values are enhanced by mature trees, and cost easements, recreational use of forests including hunting for fees and perhaps selling carbon mitigation are possible economic values of trees. The firewood value of a tree is less than its overall economic worth in enhanced value and other benefits, and there is little market for lumber from native oak trees.

There are many benefits from maintaining and planting individual trees and clusters, but one speaker suggested growers instead focus on maintaining or regenerating separate groves. “A forest is a system,” said forester Greg Giusti, from UC Cooperative Extension in Mendocino County. “You can’t combine a vineyard and an oak forest.”

While recognizing that people want to see the “museum piece giants,” Giusti recommended setting aside large tracts-- perhaps 250 acres-- to focus on creating or maintaining oak forests. “Think beyond the tree. Think of the forest.”

Few growers at the workshop can do that individually, but much of Napa County is wooded anyway: In fact, as many acres are in the county’s Land Trust as planted in vines.

Resources from the workshop will be available at naparcd.org by Thursday, March 31.