Champagne Business: Facts and Fiction(1)

Like all wines, the production and positioning of champagne is shaped by its history. Wine has been made around Reims and Epernay for over 1,500 years, and sparkling wine for over 300 years.

Like all wines, the production and positioning of champagne is shaped by its history. Wine has been made around Reims and Epernay for over 1,500 years, and sparkling wine for over 300 years.

The common story is that the fizz in the bottle was created by a blind monk, Dom Pérignon—but it is no more than a story.

A few years ago I invited a number of academics from around the world to spend four days in Champagne, France, on a study tour to investigate the wine that is made there.

The result of this exploration has recently been published in a book that I’ve edited, “The Business of Champagne: A Delicate Balance.” One of the interesting results of this exercise was to explore the myths which underpin the wine and give it meaning.

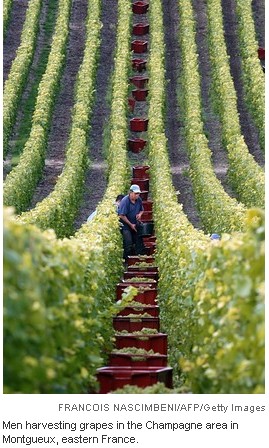

Because producing sparkling wine took time and tied up capital, in the early days it was only made by wealthy merchants, although, as was the case throughout most of Europe, the grapes were grown by many small-scale vignerons, a situation which persists until this day.

However, such was the animosity between the two groups over a range of issues (but especially the price of grapes) that one hundred years ago the vignerons rioted, attacking many of the houses owned by the merchants, responsible for the major brands, well-known on export markets.

Only subsequently, from the 1930s, did the two sides of the business decide to co-operate rather than fight.

This complex history has produced a series of paradoxes which dominate how champagne is viewed and marketed.

These paradoxes are essential for reconciling the disparate elements and aspects of the wine and the industry, but also enable the creation of a series of myths which, I believe, help establish its image externally and maintain cohesion internally in the region.

1. Simultaneous competition and cooperation.

The large champagne houses are responsible for 66% of all champagne sold (and 80% of exports). Yet they only own 10% of the vineyard area. The rest is split between over 15,000 growers who supply them with grapes.

Almost 5,000 of these growers also sell their own wine brands—many of these also selling some grapes or juice to the houses. The situation is complicated further by the existence of around 140 growers’ co-operatives, who may also sell juice or wine to the houses, but additionally can produce and market their own brands of champagne.

Supply of raw material and distribution is thus a complex process.

The houses, growers and co-operatives are mutually dependent, yet they also compete for “share of throat”—the final consumer. In this respect the champagne industry is a classic example of an industrial cluster; an environment where all benefit from proximity to each other, and where individual enterprises both compete and co-operate to their mutual benefit at the same time.