The mystery of China’s big spenders(1)

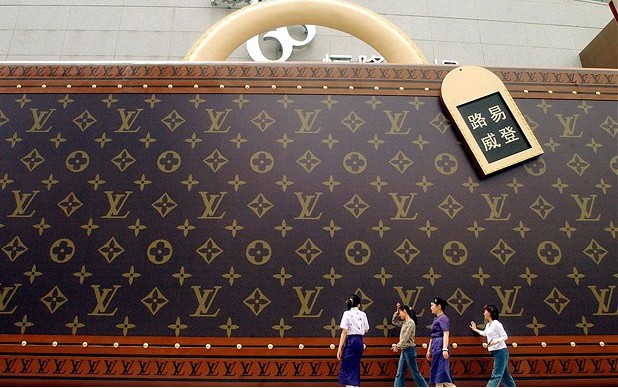

People walk past a big luggage-like advertisement of Louis Vuitton Friday June 4, 2004 in Shanghai, China. Photo: AP

They’re very picky about designer labels. They don’t spend money on DIY or lingerie. And they never, ever buy cheese. Why are Chinese consumers such complicated creatures?

During a visit to Milan some years ago, I heard about a surprising business proposal. I was with an Italian friend of mine outside his local winery and he had fallen into conversation with an old man who’d just returned from truffle-hunting in the nearby woods.

My friend runs an import-export business and was thinking about opening a sideline in exporting the fragrant nuggets of black gold to Shanghai restaurants. The concept, I said, struck me as odd as the strong flavour of truffles doesn’t sit naturally with Chinese food. But then the Italian trader told me why he thought it would work. “The Chinese will buy truffles because the Chinese will buy anything that makes them look rich,” he said.

He was right. Whether it’s a Louis Vuitton handbag or a bottle of top-flight Bordeaux, watered down with Sprite to disguise the taste, looking rich is incredibly important to China’s new consumers.

Of course, the majority of the population are desperately poor. China’s barnstorming numbers – the economy grew 9.1 per cent in the last quarter compared with less than two per cent in most Western countries – disguise the fact that one billion people live a hand-to-mouth existence in rural villages or deprived urban neighbourhoods. But this makes it all the more important, if you are a member of the emerging middle class, to underline your “superior” status.

There are, in effect, two Chinas and the need to be seen to have arrived, to be one of the 300 million consumers with money to burn, means that it’s worth sitting for hours in a traffic jam just to show off your new BMW. Or spending six months scrimping and saving to afford a Gucci bag.

“China’s consumers represent an archipelago of wealth amid a sea of rural poverty,” says Arthur Kroeber, the editor of the Beijing-based China Economic Quarterly.

More than 77 per cent of the country work the land or have menial jobs that allow them to buy little more than food and clothes. With barely two yuan to rub together, they hold no allure for the big foreign brands, or even the stronger Chinese companies. The middle class, on the other hand – whose ranks swell by millions every year – represents a potential gold mine for global brands. But, before these brands can cash-in, they need to understand who they’re selling to.

The pace at which China has grown is hard to imagine from anywhere in the West. Currently, nine million Chinese move to a city every year – the equivalent of the country building a city the size of New York on an annual basis.

China’s communist party may have come to power on the back of a peasant revolution but it has stayed in power by presiding over an industrial revolution that has done in two decades what took the West almost two centuries to achieve. In the process, the party has strayed a long way from its roots. Chairman Mao coined many pithy aphorisms, but “shop till you drop” was not one of them. Today, those born in the Seventies and Eighties under the one child policy – known in China as “Little Emperors” – have shed the frugal habits of their parents and are the driving force behind a rampant consumerism.

Even those who don’t have well-paid jobs have money, thanks to the tradition among China’s parents and grandparents of showering cash on the young. “Someone who is not rich will be given money by their parents, and grandparents, which adds up to a lot of disposable income,” says Avery Booker, the editor of Jing Daily, an internet journal which monitors China’s luxury goods market.

Most young Chinese who have migrated to the cities have come from somewhere less affluent, even if it was a smaller city rather than a rural farm, so the goods they buy serve as badges to show how far they’ve come.

“For Chinese consumers, Confucian group-think is important and at the moment they are still buying status to show that they have achieved things,” says Paul French, founder of the market research company Access Asia. “So people don’t worry that they have had to spend the past six months eating nothing but pot noodles in order to afford the newest Louis Vuitton handbag.” A designer bag retails for between £800 and £3,000 in Britain but can be around 30 per cent more in mainland China because of high import tariffs.

The lure of luxury brands is so strong that even provincial cities like Shijiazhuang, the unglamorous capital of Hebei province, in eastern China, boasts a swanky Gucci store. But, actually, it’s the appearance of mid-market brands such as Zara and H&M in second-tier cities such as Dalian, Nanjing and Chengdu that’s the surest sign of the growth of China’s middle class.

H&M, which now has 77 stores nationwide, and Zara, which has 250, do a roaring trade in the sort of safe basics, like black suits and white tops, young Chinese women love to wear. Unlike their nouveau riche counterparts in Russia, the Chinese don’t go in for zany individualism. “Not all brands are equal,” says French. “The Chinese don’t go for Versace. They don’t want the lemon shirt and the orange pants. No one wants to look like Elton John.”

Wanting to play it safe and also to make purchases which show clearly where you stand in China’s social hierarchy has its roots in the Chinese concept of “face”. This idea loosely correlates to how your appearance and conduct lead others to assess your status in society. So, coming to the office looking like Lady Gaga, when everyone else is dressed in black and white, would result in an enormous loss of face, with heavy social consequences.