These last Chinese chefs(2)

Intra-provincial diasporas also changed eating habits. Migrant workers and business professionals from all parts of China brought their regional favorites to Beijing and the other Chinese mega-cities where their skills and expertise were in demand.

This can be considered the Second Wave.

It was in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) that the four major cuisines of China were first defined, corresponding to the four busiest business hubs of that time. With better communication and transportation, the four gradually became eight - with the addition of Hunan, Fujian, Zhejiang and Anhui regional styles.

According to Dong, another four major influences were sometimes included, notably the food from Beijing and Shanghai, as well as Chinese Muslim and vegetarian cuisines.

"Exotic ingredients from outside of Beijing, and ethnic snacks from little remote places grow popular," says Dong. "Nowadays, wild mushrooms picked at 3 am in Yunnan can arrive in Beijing the same morning."

As the enthusiasm for Cantonese cuisine wanes, there is a queue of options waiting to take its place. Xinjiang restaurants, Yunnan eateries and Hunan private dining rooms are cropping up like spring grass.

The private dining rooms, especially, appeal to jaded appetites tired of daintily presented dishes on ornate plates. They offer dishes that are unique, inexpensive, and tasting of home.

Yin Zhenjiang believes Chinese dishes will no doubt evolve as time passes, with a salad bowl of regional cuisines catering to a new generation of diners and dining habits.

The traditional cuisines guarded by the master chefs will need to change as well.

"If you improve the traditional dishes and get them accepted again, that in itself will be innovation," Yin says. He thinks the move away from a planned economy has opened the way for an active and interactive culinary industry.

But the market economy also claims its victims. Take the state-run Fengze Yuan, for example. It currently faces a talent crisis because one chef who has worked here for five years gets just 2,000 yuan ($317) a month. If he moves to a private restaurant, he can easily get paid double.

For the older restaurants, change is inevitable and keeping up with the market may be the only way to survive.

The best business model now seems to point to one particular chef and his iconic restaurant - iconic only after slightly less than 10 years, hardly a blip on the timeline of Chinese cuisine.

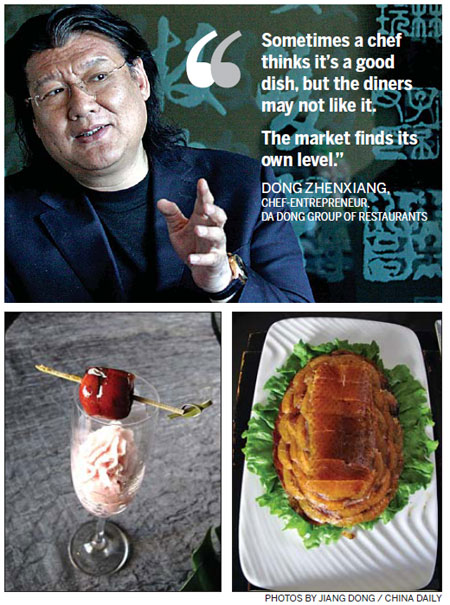

Da Dong Peking Roast Duck Restaurant, named after its charismatic chef-entrepreneur Dong Zhenxiang, serves up Peking duck and foie gras, sometimes on the same platter. A typical menu offering can be either Boston lobster served with Beijing zhajiang noodles or a cigar of Yangzhou-style rice-wine marinated crab roe and meat with chilled foie gras.

In the last decade, Da Dong has changed its menu every year. Chef Dong says his insistence on refreshing the choices offered to his customers is simple. He intends to keep them coming.

Dong is a market leader today, and his creations are praised by critics and copied by competitors. To many, he is the chef leading Chinese cuisine out of the doldrums and into an age of renaissance, but he tells us he has no such lofty ambitions, merely a desire to claim his fair share of the market.

"The only criteria is customer preference," he says. "Sometimes a chef thinks it is a good dish, but the diners may not like it. The market finds its own level."

Dong says the food at his restaurant, which he calls "artistic conception cuisine", is his response to heightened taste and palate awareness among his patrons, as well as a better appreciation of culinary lifestyle.

Dong caters to them by applying aesthetics like Chinese painting, miniature landscaping, poems and prose to his food, creating an experience that starts with the calligraphy on the menu to the delicate carvings on the plate.

He also believes in following the seasons, a concept extracted from his classical training in Shandong cuisine. So he travels to Tianmu Mountain in Zhejiang for its famous bamboo shoots and serves them fried with preserved winter vegetables in a section of bamboo, garnished with a sprig of plum blossoms.

"The direction is to learn from and follow Nature," says Dong. "What Nature has to offer is the best."

To him, fusion cooking is a natural response to changing times and China's cuisine will continue to fuse and merge just as its people will continue to migrate and assimilate.

When we ask Dong to look into the crystal ball, he says: "It will be a fusion of the different branches of Chinese cuisine. It will also incorporate healthy cooking and techniques and ingredients gathered from all over China, and the world."

Dong Keping agrees. "If Chinese food is to walk onto the world stage," he says, "it will have to be a form that is acceptable to both foreigners and to the Chinese."